The Chronicle Story of the Battle of Kulikovo

The chronicle story of the Battle of Kulikovo has survived in two versions: the short and the extended. The short chronicle story is found in chronicles that originate from the Cyprian compilation (The Trinity Chronicle). The extended story in its earliest form is in the Novgorod Fourth and Sophia First chronicles, i.e., it must have been in the protograph of these chronicles.

The short chronicle story, which appears to have been written shortly after the event (in any case not later than 1408 or 1409, the date when the Cyprian chronicle was compiled), gives the main historical facts about the Battle of Kulikovo. To take vengeance on Prince of Moscow for the defeat on the River Vozha, Mamai sets off against Russia with a large army. Grand Prince Dmitry of Moscow marches out to meet him. A bloody battle lasting a whole day is fought on the Don. The Russians are victorious. Mamai flees for his life with a small band of men. The names of the Russian princes and generals who lost their lives are listed. “Standing on their bones” Prince Dmitry pays tribute to the Russian warriors. The Russians return home with much booty. Mamai gathers together the remains of his host and prepares to march against the Grand Prince of Moscow again. But Khan Tokhtamysh attacks Mamai himself. Mamai is defeated and killed, and Tokhtamysh becomes the ruler of the Horde.

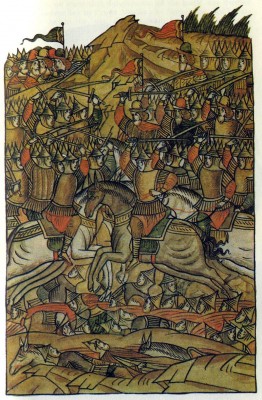

The Battle of Kulikovo in 1380. Illumination from The Illustrated Chronicle. 16th century. Academy of Sciences Library, Leningrad

Here we have a brief list of the events in chronological order. Most of the work is devoted to what happened after the Battle of Kulikovo. The battle itself is described briefly in the stock phrases of military tales: “And they sped into the fray, and the two forces met, and there ensued a long, merciless battle and cruel slaughter.” There are a few details, it is true, in the short story as well. For example, it says that the Russians pursued the enemy “to the river Mecha and there slayed a great number of them and others … jumped into the water and drowned”. The author’s attitude to what is described and his evaluation of it are expressed in brief epithets describing the Russians and Mongols and in references to Divine aid to the Russians. Mamai is “godless, impious and pagan”, Dmitry goes out to fight the enemy “for the Holy Church, and for the true Christian faith, and for the Russian land”, “And God helped Grand Prince Dmitry”, the enemy are “pursued by the wrath of the Lord”, etc.

The extended story is several times longer than the short one. It contains the text of the short one in full with a few textual changes in the first part and word-for-word reproduction of the second, main part. The extended story contains some new historical data. It describes the assembling of the Russian army in Kolomna, the arrival of Prince Andrew of Polotsk and Prince Dmitry of Bryansk, sons of Grand Prince Olgierd of Lithuania, to help the Prince of Moscow, the message sent to the grand prince on the battle field from Abbot Sergius, the crossing of the Don by the Russian army. There is a more detailed account of the battle. It says that the grand prince fought at the head of the army and that “all his armour was rent and smashed, but there was not a single wound upon his body”. There are also details and names that are not mentioned in the short chronicle story. However, the increased length of the text is due not so much to the inclusion of additional historical information and a more detailed account of this information, as to literary reasons.

The author of the extended story includes lengthy rhetorical discourses on the events he describes, drawing on religious texts for this purpose. The role of Dmitry of Moscow as the defender of Russian Orthodoxy is greatly enhanced, the contrast between the Russian army as a Christian host and the host of the “impious Mongols” is sharper and more wordy, and the negative characteristics of the latter are enhanced and expanded. The author includes several prayers by Dmitry and describes the Divine aid to the Russians in greater detail and length. The short version merely says that Oleg of Ryazan was on the side of Mamai. In the extended version this theme is developed extensively. The author returns to Oleg several times, giving details of his relations with Mamai and frequently breaking into lengthy invectives against the Prince of Ryazan. He denounces Oleg for his treachery, threatens him with retribution, and compares him to Judas and Svyatopolk the Accursed.

Until recently specialists believed the short story to be a condensation of the extended one. Marina Salmina, who has made a special study of this question, argues convincingly that the short story came first, however.14 She believes that the extended story was compiled for the compilation of 1448, from which the Novgorod Fourth and Sophia First chronicles originate (for more about this chronicle see below).

Almost all the additional historical information in the extended story can be found in some form in The Tale of the Battle Against Mamai. It is generally assumed that the Tale was created on the basis of the extended story, and, therefore, appeared later than the chronicle story. There is no convincing proof of this, however. And there are equal grounds for assuming the reverse, namely, that the extended story was written when the Tale already existed, and was influenced by it. It is quite possible also that some of the similarities in the Tale and the extended story can be explained by the influence on the various works of the Kulikovo cycle of a non-extant Lay of the Battle Against Mamai, the existence of which is argued by Alexei Shakhmatov. This question remains unsolved and requires further study.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature