The Emergence of Russian Drama and the Theatre

The Russian professional theatre appeared in 1672, the year of Peter I’s birth, as a court theatre.70 Already in the early 1660s Tsar Alexis made attempts to hire in the “German lands” and settle in Moscow a troupe of actors, “masters to make comedy” (the word “comedy” at that time was used to denote any dramatic work and theatrical production). These attempts were not successful, and eventually the founding of the theatre was entrusted to Johann Gottfried Gregory, the pastor of the Lutheran Church in the foreigners’ quarter, or German settlement, in Moscow. On the tsar’s orders he was commissioned to “make a comedy (theatrical production), and in the comedy to enact the Book of Esther from the Bible”.71

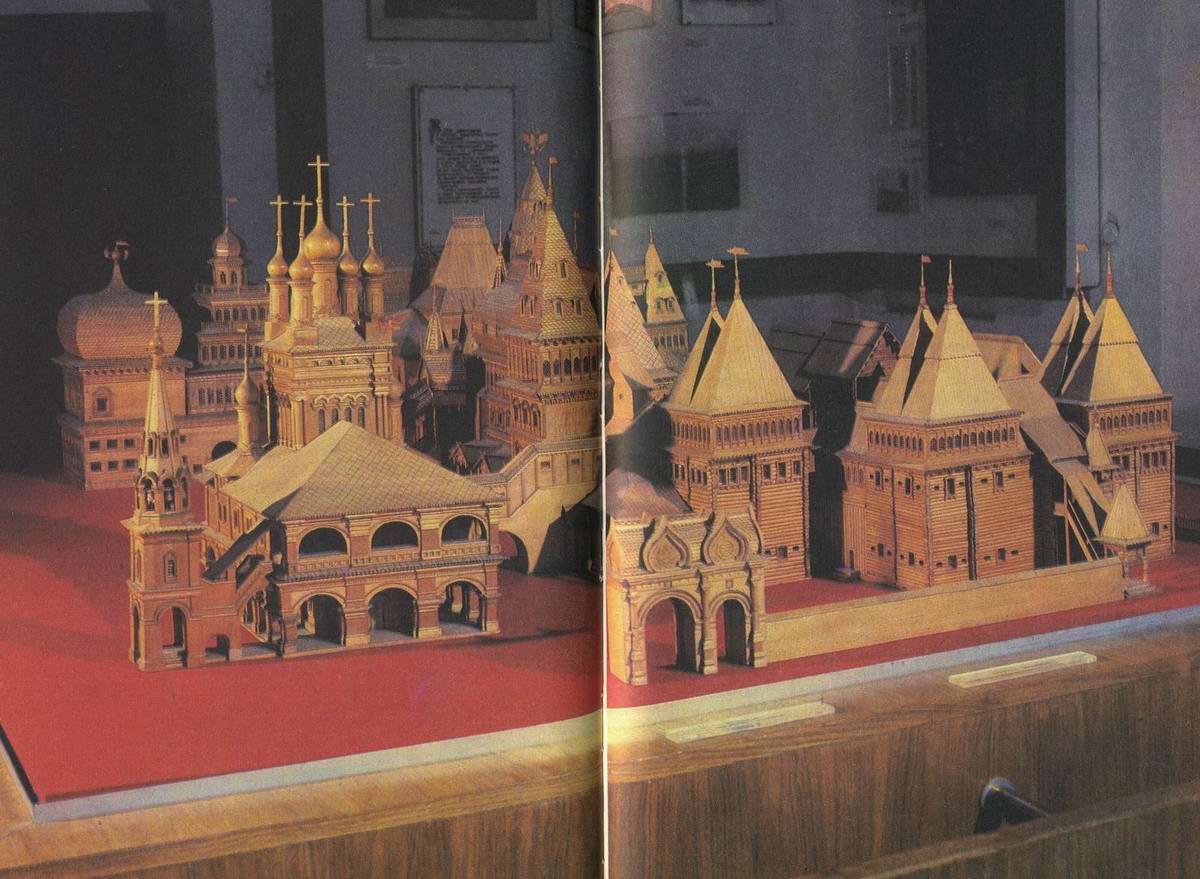

Model of the tsar’s wooden palace (1667-1671) in the village of Kolomenskoye. Kolomenskoye State Museum-Preserve of History and Architecture, Moscow

It took several months for Pastor Gregory to compose a play in German verse about the Old Testament story of the beautiful and meek Esther who attracts the attention of King Artaxerxes of Persia, becomes his wife and saves her people; for the translators of the Ambassadorial Chancery to put the play into Russian; and for the foreign actors, students of Gregory’s school, to learn their parts, male and female, in Russian. During this time a “comedy chamber” (theatre building) was erected in the village of Preobrazhenskoye, where the tsar had a country residence. The first production, The Comedy of Artaxerxes, was performed here on 17 October 1672. It was watched by the tsar, high-ranking members of the Boyar’s Council, and the tsar’s closest advisers. The Tsarina Natalia together with the royal children watched the performance from a special box behind a lattice partition.

The Comedy of Artaxerxes was performed several times. In February 1673 a new play was shown, Judith (The Comedy of Holofernes), about the Biblical heroine who kills the pagan Holofernes, leader of the army that besieges her native town. The repertoire of the court theatre was constantly being added to (performances were given sometimes in Preobrazhenskoye and sometimes in the Kremlin, in a chamber over the court apothecary). Alongside the plays on Biblical and hagiographical themes it included an historical drama about Tamerlaine who conquered the Sultan Bayazid (The Comedy of Temir-Aksak), a play which has not survived about Bacchus and Venus and the ballet Orpheus, about which we have only some very scanty information.

The actors included not only foreigners from the German settlement, but also Russian youths, mainly young scribes from the

Ambassadorial Chancery. The new royal entertainment was provided for most lavishly. There was instrumental music in the theatre (in Old Russia only singing was officially recognised, musical instruments being regarded as attributes of the wandering minstrels). There was singing and dancing on the stage. For each play “frames of perspective painting” were executed (painted sets with linear perspective, which was also a new phenomenon in Russian art). The most expensive materials and fabrics were obtained from the treasury or specially purchased for props and costumes, Persian silk, Hamburg cloth and Turkish satin.

The court theatre was Tsar Alexis’ pet creation and did not survive its founder. After his sudden death on 30 January 1676, the performances stopped, and towards the end of the year the new ruler Theodore ordered that “all comedy (theatrical) paraphernalia” be put under lock and key.

All the plays of the first Russian theatre were based on historical subjects. But they were no longer the stories about the past so familiar to readers of the Holy Scriptures, chronicles, vitae and tales. This was a showing, a visual portrayal, a kind of resurrection of the past. Artaxerxes, who, to quote the play “had been confined in his grave for more than two thousand years”, utters the word “today” three times in his monologue. Like the other personages “confined in the grave” he comes to life on the stage, speaks and moves, punishes and pardons, weeps and rejoices. For a modern audience there would be nothing remarkable about “bringing to life” a long dead potentate: this is an accepted dramatic convention. But for Tsar Alexis and his boyars, who had not received a West European theatrical education, the “resurrection of the past” in the “comedy chamber” was a real revolution in their ideas about art. It turned out that one could not only narrate the past, but also bring it to life, portray it as the present. The theatre created the artistic illusion of reality, divorcing the spectator, as it were, from reality and carrying him into a special world, the world of art, the world of history come to life.72

According to contemporary accounts, the tsar watched the first performance for ten whole hours without leaving his seat (the boyars, excluding the members of the tsar’s family, stood for the self-same “ten whole hours”, for it was not permitted to sit in the monarch’s presence). From this it is clear that The Comedy of Artaxerxes was performed without intervals, although the play was divided into seven acts and a large number of scenes. No intervals were allowed because they might have destroyed the illusion of “resurrected history” and brought the spectator back from the “artistic present” to the real present, whereas it was precisely to create this illusion that the first Russian theatre-lover had built the “comedy chamber” in the village of Preobrazhenskoye.

It was not easy to get used to theatrical convention. This can be seen albeit from information about the costumes and props. They used not theatre trumpery, but expensive cloths and fabrics, because at first it was hard for the audience to grasp the essence of acting, the essence of the “artistic present”, difficult for them to see Artaxerxes as both a real “resurrected potentate” and a German mummer from the foreigners’ settlement. The author of the play found it necessary to mention this in the foreword which was addressed directly to the tsar:

“Thy sovereign word makes Artaxerxes, as it were, alive, in the form of a youth…”

The foreword was written specially for the Russian audience and “recited by a special character called Mamurza (‘the tsar’s orator’). Mamurza addresses the most important member of the audience, Tsar Alexis, and explains the artistic essence of the new entertainment to him: the problem of the artistic present, how the past becomes the present before the tsar’s eyes. Mamurza has recourse to the concept of “glory” which had long been associated in Old Russia with the idea of the immortality of the past. Clearly and intelligibly he explains to Tsar Alexis that his glory too will remain forever, like the glory of many historical heroes… In order to help the tsar perceive people of the past as being alive, the author makes these people feel that they have been resurrected. Not only do the audience see historical figures before them … but the figures themselves see the audience, marvel at how they got there, and admire the tsar and his realm… In his brief explanation of the content of the play, Mamurza does his best to draw the audience into the unfamiliar atmosphere of the theatre and stress the marvellous nature of the repetition of past events in the present.”73

So the theatre created the artistic illusion of life. But what kind of life did the Russian spectator see before him? What sort of people did he see on the stage? Although they were “resurrected” from the past, they bore a remarkable resemblance to those who were sitting (or standing) in the “comedy chamber”. The characters were in perpetual motion. They were remarkably active and energetic.74 They urged one another to “hurry”, “tarry not”, “effect quickly”, “make haste”, “waste not time”. They were not meditative. They “knew their job well”, “got down to work”, and “despised the slothful”. Their life was packed to the full. “Resurrected history” was portrayed as a kaleidoscope of events, an endless chain of actions.

The “active man” of early Russian drama was in keeping with the style of behaviour that arose on the eve of and particularly during the period of the Petrine reforms. During this period the old ideal of “comeliness”, “propriety” and “decorum” collapsed. Whereas in the Middle Ages it was considered proper to act calmly and deliberately (kosno) without “intense and bestial zeal”, now it was positive to be energetic. It was in the latter half of the seventeenth century that the word kosnost acquired a pejorative meaning.

Tsar Alexis chose efficient men and demanded constant diligence from them: “Be ever assiduous and vigilant all the while, constantly on the alert and keep your wits about you.”75 In carrying out their sovereign’s commands, his “close” advisers, such as Afanasy Ordin-Nashchokin or Artamon Matveyev, laboured ceaselessly “without respite”.

The life that the visitors to the court theatre watched on the stage was certainly not conducive to repose. It was a motley, changeable life, in which transitions from grief to joy, merriment to tears, hope to despair and vice versa were quick and sudden. The characters in the plays bemoaned “fickle”, “accursed”, “treacherous” luck, Dame Fortune whose wheel raises some and casts down others. The “resurrected world” consisted of contradictions and antitheses.

The tsar’s new amusement was not only entertainment (“comedy can cheer a man and turn all human care into joy”), but also a school in which one could “learn many good … lessons in order to renounce wrong-doing and embrace that which is good”. The theatre was a mirror in which the spectator recognised and understood himself.

Many ideas of European Baroque were reflected in this mirror, first and foremost, its favourite postulate that life is a stage and people are the actors. In the mirror one could also see a certain reflection of Russia in the process of Europeanisation, as with extraordinary energy she joined in concert with the great European powers on equal terms. The official culture of the latter half of the seventeenth century shows a high degree of confidence in Russia’s success and in the greatness of its historic mission. This explains why Russian art of this period, in drawing on the experience of European Baroque, took mainly that which was positive and optimistic. The world of court poetry and court drama is a fickle world, full of conflicts and contradictions. But in the final analysis good and justice triumph, harmony is restored and peoples and countries rejoice and prosper.

The type of professional writer and convinced humanitarian represented by Simeon of Polotsk, Sylvester Medvedev and Karion Istomin did not immediately disappear in the Petrine age. Stefan Yavorsky (1658-1722), locum tenens of the patriarchal throne and later president of the newly instituted Synod, was such a person, a brilliant orator and poet, who in his youth had been crowned with the title of poet laureate at the Kiev-MogilaAcademy. So was Dimitry of Rostov (1651-1709), a playwright, composer of fine lyrical verse, and prolific prose writer, who is famous for the multi-volume Great Menology. But gradually Peter the Great relegated the Baroque humanitarians into the background. He had no need of them for a variety of reasons.

The very type of Baroque writer from the “Latiniser” school seemed to Peter to be an obstacle to transforming Russia. According to the Baroque philosophy of art, the poet was accountable only to God. Dimitry of Rostov, who compiled The Great Menology as he had vowed he would, ordered that the draft of this great work be placed in his coffin, so that he could use it to justify himself in his future life. Peter, however, believed that poets were answerable not to God, but to the tsar, that they did not form the elite of the nation and were no different from any other subject. All inhabitants of Russia were accountable to Peter and the state.

Peter broke with the “Latinisers” also because the culture that they fostered was of an exclusively humanitarian nature. Peter’s reforms were imbued with the idea of usefulness, and there was no usefulness, no direct, immediate, palpable benefit from the “Latinisers”. Peter advanced a different type of writer. The intellectual, who composed in keeping with a vow or his inner convictions, was replaced by the servant who wrote when commissioned or ordered. Peter promoted a new type of culture. Whereas for the “Latinisers” who created Moscow Baroque poetry was the queen of the arts, now in the Baroque of St Petersburg it was the servant of the natural sciences and practical disciplines. Poetry turned into an embellishment of “useful” books, such as Leonty Magnitsky’s Arithmetic in which mathematical rules were attired in rhythmical speech.

Whereas in the time of Simeon of Polotsk and his pupils the whole world, all the elements of the universe, including man, were perceived as the Word, now the word too became a thing. From Simeon of Polotsk’s “Museum of Rarities” to the St Petersburg Kunstkammer, a real museum of monstrosities and curiosities— this was the evolution of Russian Baroque. The Word was the symbol of Moscow Baroque, but the symbol of St Petersburg Baroque was the Thing.

Under Peter Russia produced many new things for the first time in its history—a fleet, a theatre open to the general public, an Academy of Sciences, parks and park sculpture; it also produced new clothes, new manners, a new style of social behaviour, and even a new capital. The production of things replaced the production of words, which is why the Petrine period is sometimes called the “most unliterary” period in Russian history. Did this mean the decline of literature? The answer is yes, it did, in a certain sense.

There was naturally a deterioration in style, language became macaronic and borrowing and barbarisms abounded. The world of the Russian was in a state of rapid transformation. These changes had to be recorded immediately, more and more new things had to be “given names”, and this was done by “bad” style. Literature ceased to be professional. Whereas under Tsar Alexis writing was the prerogative of people with a good humanitarian education, under Peter a tribe of dilettantes multiplied rapidly. The following example illustrates the extent of this dilettantism: in the Petrine period poems (in the genre of the love elegy) were composed by society ladies in St Petersburg from such noble families as the Cherkasskys, Trubetskoys, etc. The Empress Elizabeth herself was active in the field of pursuit of poetry. Dilettantism is a symptom of decline.

Yet there were also positive elements in all this. The secularisation of culture, its freeing from the tutelage and control of the Church, resulted in the liberation of subject matter and plot. Literature not only served practical aims; it also entertained, and under Peter the bans were lifted on humour, merrymaking and the theme of love, which were topical not only in the Middle Ages, but also in the period of Moscow Baroque. Outside state commissions a writer was free in his choice of themes and plots, in so far as he was not bound by religious ideology. This “literary step forward” was also a reform in its way, and a reform with far-reaching consequences.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature