The Tale of the Campaign of Stephen Bathory Against Pskov

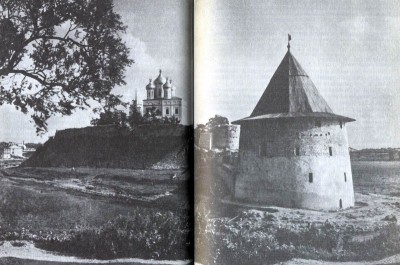

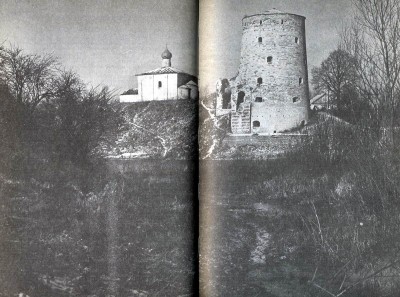

The last sixteenth-century tale appeared after the death of Ivan the Terrible. It is the historical Tale of the Campaign of Stephen Bathory Against Pskov. Like the historical tales of the fifteenth century, it had a single theme. That theme was the siege of Pskov by King Stephen Bathory of Poland in 1581.24

After a short account of the beginning of the war the author turns to the siege of Pskov by Polish-Lithuanian forces. The king, whom the author of the tale portrays like a “ferocious monster” out of a folk tale, encircles the city and is gloating prematurely over his victory. The enemy bring up siege towers and manage to capture the Intercession and Swine towers: the Polish flag is hoisted on both of them. But the people of Pskov pray, and God hears their prayers. The Russians attack the SwineTower, put gunpowder under it and blow it up. “Are my nobles in the castle yet?” asks Bathory. “No, Sire, they are under the castle,” is the reply. Not understanding this, the king decides that they must be by the city walls, fighting the Russians. “Sire! All those in the SwineTower have been killed and burnt to death, and lie in the moat,” he is told. The enraged king orders his men to advance through the breach in the wall and take the city. But the Russians resist the assault, monks and women fighting together with the men, and drive the enemy out of the city. Pskovian women help their husbands by dragging abandoned Lithuanian arms into the city.

The first assault has been unsuccessful, but the boyars and commanders remind the people of Pskov that fresh battles lie ahead. Having failed to take Pskov directly by siege, Stephen fires a message over the city walls on an arrow, inviting the townspeople to surrender “the city without bloodshed” and threatening “all manner of cruel deaths” if they do not. The people of Pskov reply in the same vein declaring that “not even the most feeble-minded in the city of Pskov” would accept this advice.

The king begins to dig underground passages under the town; the Pskovians learn of this from enemy soldiers who have been captured or changed sides. The Russians dig underground passages and blow up the enemy’s passages. The last assault on the city, over the ice of the River Velikaya, is also unsuccessful. The king withdraws from Pskov, leaving his chancellor (Zamoisky) in his place. Not expecting to overcome the Pskov voevoda Ivan Shuisky in fair combat, the chancellor resorts to a foul trick. He sends Shuisky a casket, assuring him that it contains money. But the trick does not work. Shuisky orders one of his men to open the casket some distance away from his headquarters, and it is found to contain gunpowder with a “self-firing” device. The chancellor withdraws from Pskov “in great haste”; the siege is lifted, and the city gates, closed at the beginning of the siege, are opened.

Stylistically The Tale of the Campaign of Stephen Bathory Against Pskov is very reminiscent of such sixteenth-century works of historical narrative as The Book of Degrees and The History 0f Kazan. Here too high-flown conventional formulas are used rhetorical addresses to the characters and the reader, and so on. But for all its traditional elements The Tale of the Campaign of Stephen Bathory, like other works of historical narrative, was to some extent influenced by the fictional literature of the fifteenth century (the author of the tale quotes the Alexandreid and Stefanit and Ikhnilat.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature