The Writings of Archpriest Avvakum

Whereas mediaeval literature is characterised by a relative unity of artistic system and artistic taste, a kind of “style of the age”, in the seventeenth century this unity is destroyed. The individual element is felt increasingly strongly in art. Literature turns into an arena for conflicting ideas, and the writer becomes an individual, with his own, unique creative manner.54

Most vividly of all the individual element is found in the writing of Archpriest Avvakum (1621-1682). This famous leader of the Old Believers became a writer somewhat late in life. Before the age of forty-five he took up his pen rarely. Of all his writings that have so far come to light (about ninety),55 barely ten belong to this early period. All the rest, including his famous Life, the first lengthy autobiography in Russian literature, was written in Pustozersk, a small town at the mouth of the River Pechora, in “the freezing, treeless tundra”. It was here on 12 December, 1667, that Avvakum was brought and imprisoned, here that he spent the last fifteen years of his life, and here, on 14 April, 1682, that he was burnt to death “for greatly abusing the tsar’s house”.

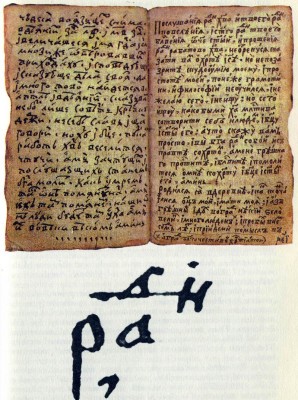

Pustozersk Miscellany. The end of the Life of Archpriest Avvakum and the beginning of the Life of Epiphanius. Autographs. Late 17th century. Institute of Russian Literature, Leningrad

In his younger years Avvakum had not intended to devote himself to literature. He chose a different field, that of fighting against the abuses committed by Church and State, the field of the spoken sermon, of direct contact with people. The robe of the priest (which Avvakum received at the age of twenty-three, when he was still living in his native parts “within the bounds of Nizhny Novgorod”), and then of archpriest made such contact possible for him. People filled his life. “I had many spiritual children, five or six hundred by then. And I, poor sinner, toiled without rest in churches, and in folk’s homes, and on journeys, preaching around towns and villages, and in the capital, and in the land of Siberia.”

Avvakum never changed his convictions. In spirit and temperament he was a fighter, a polemicist, a denouncer, and he exhibited these qualities throughout his life and labours. His first clash with the church authorities came in 1653, when he was serving in the Kazan Cathedral in the Kremlin (“I liked it in the Kazan Cathedral. I read books to the people there. Lots of folk used to come.”) On the eve of Lent Nikon, who had been made Patriarch a year before, sent a “memorandum” to the Kazan Cathedral, and then to the other Moscow churches instructing people to cross themselves with three fingers instead of the usual two. This memorandum marked the beginning of the Church reform. Avvakum disregarded Nikon’s order and, naturally, could no longer serve and preach in the Kazan Cathedral. So he assembled the parishioners in a barn. His supporters said openly: “There are times when a stable is better than a church.”5 The recalcitrant archpriest was enchained in the Andronicus Monastery in Moscow. This was Avvakum’s first taste of imprisonment: “They cast me into a dark place in the ground and I sat there for three days, neither eating nor drinking; sitting chained in darkenss I bowed, not knowing whether it was to the east or the west. No one came to me but mice and cockroaches, and the crickets chirped, and there were plenty of fleas.”

Shortly afterwards he was sent to Siberia with his wife Nastasia Markovna and their children, first to Tobolsk, then to Dauria. But exile in Siberia (which lasted eleven years) did not break Avvakum, just as all the terrible suffering that fell to his lot later did not break him either.

Meanwhile Avvakum’s enemy, Nikon, was forced to relinquish the patriarchal throne in 1658, because Tsar Alexis no longer could or would tolerate the high-handed tutelage of his former personal friend. When Avvakum was brought back to Moscow in 1664, the tsar sought a reconciliation with him: he needed the support of this man whom the people already acknowledged as their protector. But nothing came of this attempt. Avvakum hoped that the removal of Nikon would mean a return to the “old belief”, but the tsar and the leading boyars had no intention of renouncing the Church reform, because it was an essential link in the irreversible process of the Europeanisation of Russia. The tsar soon realised that Avvakum was a danger to him, and the recalcitrant archpriest was again deprived of his freedom. Then followed new exiles, monastery imprisonments, defrocking and excommunication by the Church Council of 1666-1667 and, finally, incarceration in Pustozersk.

It was here that the preacher became a brilliant writer. In Pustozersk he had no congregation. He could not preach to his “spiritual children”, and there was nothing left for him but to take up his pen. The ideas that he had conceived way back in his youth and that he had sought to impress upon the people in “the bounds of Nizhny Novgorod”, the Kazan Cathedral, the Moscow barn and Dauria, he now defended staunchly in his writings.

In Pustozersk Avvakum lived with three other exiled leaders of the Old Believers—Epiphanius, a monk from the Solovetsky Monastery, Lazarus, a priest from the town of Romanov, and Theodore Ivanov, a deacon from the Cathedral of the Annunciation in Moscow. Together they were burnt to death. They were all writers. Avvakum was very close to Epiphanius, his confessor. At first the Pustozersk prisoners lived comparatively freely and were able to communicate with one another. They quickly established contact with their followers in Moscow and other towns. The Streltsy, who sympathised with these sufferers for the “old belief”, willingly helped them. “And I told them to make a secret hole in the handle of a Strelets’ pole-axe,” Archpriest Avvakum wrote to the boyar’s wife Feodosia Morozova in 1669, “and with my own poor hands put the missive in the pole-axe … and bowed low to him and asked him to take it, protected by the Lord, to my son (his son was imprisoned on the River Mezen—A.P.) and the elder Epiphanius made the secret hiding place in the axe.” Epiphanius, who could turn his hand to anything, also made many wooden crosses with secret compartments in which he hid “letters” sent “into the world”.

These seditious writings were sent of to the Mezen, where Avvakum’s family was living, and from there went further afield. Avvakum even managed to establish contact with the Solovetsky Monastery, which refused to accept Nikon’s “innovations” and was besieged by tsar’s troops in 1668. In 1669-1670 he wrote to the Mezen, where his devoted pupil, Theodore the Fool-in-Christ, was living with Avvakum’s family: “Let Theodore conceal these letters and go to the Solovetsky Monastery, enter it secretly and deliver the letters.”

Seeking to put an end to the activities of the “great four”, the authorities resorted to punitive measures. Ivan Elagin, a high- ranking officer, was sent to the Mezen and to Pustozersk. On the Mezen he hanged Theodore and in Pustozersk in April 1670 he “meted out punishment” to Epiphanius, Lazarus and the deacon Theodore: their tongues were cut out and their right hands severed. Avvakum was spared. “And I wouldn’t abide that and wanted to die of hunger,” wrote Avvakum, “and I did not eat for eight days or more, but the brethren bade me eat.”

After that the conditions of his imprisonment deteriorated sharply. The guards, Avvakum wrote, “placed timber frames around our pits and filled them up with earth … leaving us each one small opening through which to get food and firewood.” Avvakum described his “large room” with bitter irony: “Both I and the Elder (Epiphanius) have a large room … where we eat and drink, and … defecate too, yes, on a spade, and then out of the window! I think the Tsar Alexis, son of Michael, does not have such a spacious chamber.”

But the intolerable conditions of this “pit prison” did not weaken the Pustozersk exiles’ urge to write, particularly as the demand for their works was tremendous. The words of Avvakum and his followers possessed great moral authority for Old Believers. They were surrounded by the aura of martyrdom for the faith. Their works were copied and disseminated secretly. The “great four” laboured hard, writing more and more new works.

In Pustozersk Avvakum wrote a large number of petitions, letters and epistles, as well as such lengthy works as The Book of Talks (1669-1675) which contains ten discourses on different dogmatic subjects; The Book of Interpretations (1673-1676) which contains Avvakum’s interpretations of the Psalms and other Old Testament texts; and The Book of Denunciations, or the Eternal Gospels (1679), containing Avvakum’s theological polemic with the deacon Theodore, his co-prisoner. In Pustozersk Avvakum also produced his monumental autobiography, the splendid Life (1672), which he revised several times.5

In origins and in ideology Avvakum belonged to the common folk, the lower strata of society. Both his sermons and his literary work were full of democratic spirit. His long and bitter experience had convinced Avvakum that life was hard for common folk in Russia. “Even without the flogging a man finds it hard to keep going,” he writes in his Life, recalling his enforced journey to Dauria. “But the slightest excuse and he gets a touch of the stick: ‘Stay where you are, fellow, die on the job!”’ The idea of equality is one of Avvakum’s favourite ideas: “There is one heaven, and one earth, and bread belongs to all, and water too.” He saw Russian people as his brothers and sisters “of the spirit”, not recognising any differences of estate. “Are you any better than us because you are a boyar’s wife?” he asks Feodosia Morozova. “The Lord has spread out the sky for all of us, and the moon and the sun shine alike for each and every one, and the earth, the waters, and all that grows at the Lord’s behest does not serve you more or me less.”

Here, of course, Avvakum is quoting the letter and spirit of the Gospels. But in relation to Russian life of the seventeenth century the idea of equality acquires a secular, rebellious note. For Avvakum Christians are the common people, and he accuses the Church pastors and secular rulers of Nikonianism, saying they have turned into wolves that devour their “hapless victims”. “Not only for the changing of the holy books,” writes Avvakum, “but also for secular truth … it is proper to lay down one’s life.”

Avvakum’s ideology is full of democratic spirit. The same democratic spirit imbues his aesthetics, determining the linguistic standards, representational means, and writer’s standpoint in general. Avvakum constantly has the reader before him as he writes. He is either a peasant or artisan with whom Avvakum had dealings in his younger years. He is Avvakum’s spiritual son, careless and diligent, sinful and righteous, weak and strong at one and the same time. He is a “true son of his people”, like the archpriest himself. Such a reader would find it difficult to understand the intricacies of Church Slavonic. You have to speak to him simply, and Avvakum makes the vernacular his stylistic principle: “Readers and hearers, do not despise our popular speech, for I love my native Russian tongue… I shall not concern myself with rhetoric and do not disparage my Russian tongue.”

It must be said that in all his works, the Life in particular, Avvakum shows exceptional skill as a stylist. He has an extraordinarily free and flexible command of the “native Russian tongue”. One of the reasons for this is that Avvakum feels he is talking, not writing (“But why say so much?”, “But that’s enough talk!”, “Shall I tell you another story, my friend?”). He is talking to his audience, continuing the work of preaching in his distant “pit prison”. He calls his manner of exposition “blathering” and “growling”.

Avvakum’s style is highly emotional. Sometimes he addresses his reader-hearer affectionately as “father”, “dear one” “poor creature”, “my dear”, “Alexei dear”, “dear Simeon”, and sometimes he rebukes him, as he rebukes the deacon Theodore, his opponent on theological questions: “You’re a real fool, Theodore!” A sad pathos echoes in his words to the boyar’s wife Feodosia Morozova, who was dying of hunger in prison in Borovsk: “Are you still breathing, my light? Are you still breathing, dear friend, or have they burnt you, or strangled you? I know not and hear not; I know not if you are alive or they have put an end to you! Child of the Church, my dear child, Feodosia Prokopievna! Tell me, an old sinner, but one word: are you alive?” But nor does he eschew humour—he ridicules both his enemies, calling them “unfortunates”, “poor wretches”, and “fools”, and himself, even when he is describing the most tragic episodes of his life.

Recalling in the Life how he was defrocked, “shorn”, Avvakum writes about it with humour: “They tore my hair out like dogs, leaving nothing but a tuft, like the Poles have, on my forehead!” This is what he has to say about his sufferings in Dauria: “For five weeks we travelled in sledges over the bare ice. I was given (by the governor Afanasy Pashkov) two nags to carry the children and our poor belongings, and me and the wife went on foot, stumbling over the ice. It’s a wild country and the natives are a savage lot; we dared not fall behind the horses, but we couldn’t keep us with them, hungry and tired as we were. The poor wife trudged along and kept falling down, it was so slippery! One day she fell down and some poor tired fellow stumbled over her and fell; the two of them were shouting for help and couldn’t get up. ‘Forgive me, mistress!’ the man cried. ‘Why did you knock me down, man?’ cried the wife. I came up, and the poor woman reproached me, saying: ‘How long must we bear this torment, Archpriest?’ And I said: ‘Till death itself!’ Then she sighed and answered: ‘Very well, let’s be on our way then.”’ This episode gives a good idea of the nature of Avvakum’s humour. On the one hand, it is “fortifying laughter” at the most difficult moments, healing laughter that helps one endure tribulations with dignity. On the other hand, it is gentle self-mockery that saves one from self-conceit and false pride.58

This is essential from the point of view of both Avvakum and his reader, because Avvakum’s main hero is himself. This is the first time in Old Russian literature that the author writes so much about his own hardships, about how he “grieves”, “sobs”, “sighs”, and “laments”. This is the first time that a Russian writer dares to compare himself to the first Christian writers—the Apostles. “Perhaps I should not have spoken about my life, but I have read the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles of Paul—and the Apostles did speak of themselves after all.” By quoting the authority of the Apostles, Avvakum willy-nilly declared himself also to be an Apostle. He called his Life “the book of eternal life”, and this was no slip of the tongue. As an Apostle Avvakum could write about himself. He was free in his choice of themes and personages, free to use “popular speech” and to discuss his and others’ actions.

In writing his Life Avvakum observed the hagiographical canon to some extent. The exposition, as the canon required, contains an account of the parents and childhood of the hagiographical hero. It also describes the first sign that the hero received, the “vision of a ship”: “And then I saw … a ship, adorned not with gold, but with many colours—red, white, blue, black and grey—the human mind cannot encompass how fair and sound it was. And a radiant youth sat at the stern steering it… And I cried out: ‘Whose boat is this?’ And the youth replied: ‘It is your boat! Go sail in it with your wife and children, if you so wish!’ And I began to tremble and thought to myself: ‘What can this mean? And where shall I sail?”’ The sea is life and the ship a man’s fate. These are mediaeval images, and they run all through the Life. Behind every event Avvakum sees a hidden, symbolic meaning, and this too brings him close to Old Russian hagiography. The Life ends with a description of the punishment of 1670 in Pustozersk. But this is followed by episodes from Avvakum’s life that are not connected with the main plot and in composition and subject matter recall the “miracles” that are always appended to the Old Russian vita.

Nevertheless Avvakum radically reforms the hagiographical scheme. For the first time in Russian literature he unites the author and the hero of the hagiographical narrative in the same person. From the traditional viewpoint this is impermissible for it is sinful pride to extol oneself. The symbolism of the Life is also personal. Avvakum gives a symbolical meaning to “transitory” everyday details, that mediaeval hagiography generally ignored.

Speaking of his first imprisonment in 1653, he writes: “I had not eaten for three days and felt hungry. After vespers someone appeared before me. I did not know whether it was an angel or a man, and do not know to this day; only he prayed in the darkness and, putting his hand on my shoulder, led me with the chain to a bench and sat me down on it. And he put a spoon into my hand, and a little bread, and gave me cabbage soup to eat—it was so good and tasty! And he said to me: ‘Eat and fortify yourself.’ And then he was gone. The door did not open, but he was gone! That is strange if it was a man, but what if it were an angel? Then it is not surprising, for nothing bars his way.” The “miracle of the cabbage soup” is an “everyday miracle”, like the story of the black hen that fed Avvakum’s children in Siberia: “Each day it laid two eggs for our children to eat, helping us in our need at the Lord’s behest, for the Lord so ordained.”

The symbolical interpretation of everyday details is extremely important in the system of ideological and artistic principles of the Life. Avvakum fought hard against Nikon’s reform not only because Nikon had violated the Orthodox ritual hallowed by centuries. He also regarded the reform as a violation of Russian customs, the whole Russian way of life. For Avvakum Orthodoxy was firmly bound up with this way of life. If Orthodoxy were destroyed, Russia would perish too. That is why he describes Russian life so affectionately and vividly, particularly family life.

Avvakum’s Life is not only a sermon, but also a confession.59 One of the most striking features of this work is its sincerity. This is not only the standpoint of the writer, but also of the sufferer, the “living corpse”, who has settled his account with life and for whom death is a blessed release. “What do I need, sitting in my prison, as in a coffin? Can it be death? Truly, it is so.” Avvakum detests falsehood and pretence. There is not a single false note in his Life, nor in the rest of his writing. He writes nothing but the truth, that truth which his “enraged conscience” dictates to him.

Avvakum does not vary his sincerity in relation to the reader, the person he is addressing. In this respect his wife, the boyar’s wife Morozova and the tsar himself were all the same to him. “And I shall order that Tsar Alexis be called to judgment before Christ,” wrote Avvakum. “Let him be scourged with copper lashes.”60 When Tsar Alexis died and the throne went to his son Theodore, Avvakum sent the new ruler a petition in which he requested: “Have mercy on me, who have no refuge and am estranged from God and from people for my sins, have mercy on me, son of Alexis, fair child of the Church!” But even in this petition Avvakum did not fail to rebuke the late tsar—in his letter to the son who had just lost his father! “God will be the judge between me and Tsar Alexis. For I have heard from the Saviour that he sits in torment.”

In order to judge Avvakum as a fighter, a rebel, we should recall his connection with the act of protest of the Moscow Old Believers during the traditional ceremony of the Blessing of the Waters in 1681. When a large crowd of people had assembled in the Kremlin, the Old Believers “shamelessly and furtively threw down blasphemous scrolls that dishonoured the tsar’s dignity”61 from the bell-tower of Ivan the Great, and smeared tar on the church robes and tsars’ tombs in the Cathedral of the Assumption. Among the “furtive scrolls” were writings by the Pustozersk prisoners. Avvakum, who could draw as well as write, also portrayed “their majesties the tsars and high-ranking church leaders” on birch bark with “abusive captions” and “highly forbidden” words. It was these caricatures that the Old Believers distributed during the tsar’s procession to the hole in the ice of the River Moscow during the ceremony.

Having lost faith not only in Tsar Alexis, but also in his heir and realising that the Moscow rulers had renounced the “old belief” once and for all, Avvakum turned to openly anti- governmental propaganda. This is why he was burnt at the stake—not only for the Schism^ but also “for greatly abusing the tsar’s house”.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature