Translated Tales

Translated Tales. Fifteenth-century tales, unlike earlier ones, not only tell of historical events and famous figures in Russian history, but of all sorts of people whose lives contain events of interest to the reader. They were works of fictional prose, intended for reading, without any official or religious purpose. Translated works of this type had been known in Russia earlier (The Tale of Akir the Wise, for example), but in the fifteenth century there were far more of them than before.

The Serbian Alexandreid. Of all the translated tales that appeared in Russia in the latter half of the fifteenth century, mention must be made, first and foremost, of the so-called Serbian Alexandreid, a romance about the life and adventures of Alexander the Great.20 This romance came to Russia in the fifteenth century and became more popular than The Chronographical Alexandreid.

The earliest Russian manuscript of The Serbian Alexandreid was transcribed by a monk in the White Lake Monastery of St Cyril, Euphrosyne. The Serbian Alexandreid appears to derive from a Greek original of the third or fourth century, but it came to Russia in a South Slavonic (Serbian) version. The Serbian Alexandreid differed from The Chronographical Alexandreid in several important respects. In the Serbian version Alexander is credited with the conquest of Rome and Jerusalem. He also visits Troy and pays tribute to the heroes of Homer’s Iliad, but at the same time he worships the one and only God and is friendly with the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah. The features of the mediaeval romance were greatly enhanced in The Serbian Alexandreid: the theme of the love of Alexander and Roxana (which is not found in The Chronographical Alexandreid or other tales about Alexander) is a major one here: Alexander tells his mother that this love that “conquered” his heart made him think for the first time of domestic matters and the Macedonians. When Alexander dies, Roxana kills herself.

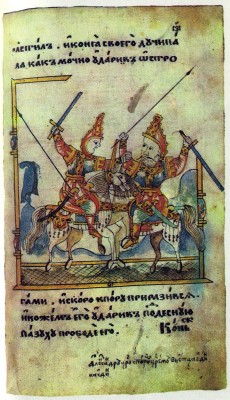

Battle of Alexander the Great and King Porus. Illumination from a 17th-century manuscript copy of the Alexandreid. State Public Library, Leningrad

The tale opens with a description of Alexander’s “miraculous” birth. As in The Chronographical Alexandreid, his father is not Philip of Macedonia, but the Egyptian King and magician Nectanebes. At his birth it is predicted that Alexander will be king of the whole universe known for his “piety, joy, and wisdom”, but will live not more than forty years.

After Philip’s death Alexander becomes an “autocrat”, conquering “Athens the Wise” and other Greek lands, then waging war against King Darius of Persia.

In the romance Alexander is constantly putting himself in perilous situations, challenging fate “sticking his neck out”, as his generals put it. He dresses up in other people’s clothes, now in the guise of a close friend, now as his own envoy. He even makes so bold as to visit Darius himself, dressed up as the Macedonian envoy, on the eve of the decisive battle with the Persians. At the feast in Darius’ palace the disguised king drinks the wine offered to him and hides the goblet under his robes. After deceiving the Persians, he hurries to leave the palace and uses the goblet to help him to get through the gates. “Here, take this goblet! King Darius has sent me to inspect the guard,” he says curtly to the gate-keepers, who believe him and let him through.

The account of Alexander’s visit to Darius is followed by a description of the decisive battle between them. Darius is beaten, and his treacherous counsellors stab him and leave him by the wayside. There he is found by Alexander and carried to the royal palace. Whereas in the scenes describing Alexander’s adventures and exploits the speech of the characters is laconic and expressive, in the scenes portraying strong emotions it is lengthy and rhetorical. On being found more dead than alive by Alexander Darius can “barely breathe”, but this does not stop him from speaking in a most protracted, high-flown fashion. Eventually, “after much weeping”, Darius gives his daughter Roxana to Alexander in marriage and dies. Alexander buries Darius with “great honour” and executes his murderers. After his victory over Darius Alexander is equally successful in defeating the Indian ruler Porus and then sets off to journey round some strange lands. During this journey he visits, among other things, the cave of the dead, where he meets his vanquished opponents, Darius and Porus.

The twists and turns in the hero’s fate could not fail to enthral the reader of the Alexandreid. Not knowing the outcome of Alexander’s adventures, the reader lived every moment of them in thrilled suspense and rejoiced when they ended happily. At the same time the theme of the transience and impermanence of all human achievements is constantly reiterated in the romance. The successes won with such difficulty and danger amount to nothing in the end, and the early death predicted for Alexander at his birth is not to be avoided. During his travels Alexander visits the Brahmins who live close to paradise and are called nagomudretsi (“naked wise men”), because they are nagi (“naked”), i.e., completely lacking not only in clothes, but in all belongings and “all passion”. Alexander offers to give them anything they do not have in their land. “Then give us immortality, King Alexander, for we are mortal!” exclaim the Brahmins. “I am not immortal; how shall I give you immortality?” the king replies. The only thing the Brahmins need is something that Alexander does not possess either. “Go in peace, Alexander, conquering the whole earth, yet in the end you yourself will lie in it,” the Brahmin elder says to him. This theme recurs over and over again in the romance. “Oh, most wise of men, Alexander,” Darius asks in the cave of the dead, “are you too doomed to join us?” At the end of the romance the prophet Jeremiah appears to Alexander in a dream to announce that his death is nigh, and Alexander has a final inspection of his army. The description of this inspection is one of the most powerful scenes in the work. Past the doomed general march his victorious soldiers: Greeks, Macedonians, Egyptians, all the peoples that make up his army. Looking at them, Alexander shakes his head and says: “Do you see them all? Fifty years hence they will all be in their graves!”

Although the time of Alexander’s death has been foretold in advance, its cause is unexpected. Alexander is treacherously poisoned by his cup-bearer. Like the description of Darius’ death, the account of Alexander’s last days is high-flown and moving. The poisoned emperor grows numb and begins to “tremble”, but still utters lengthy speeches to his generals, Roxana and even the wicked cup-bearer. When he dies, Roxana laments her “Macedonian sun” and stabs herself to death over her husband’s coffin. Alexander and Roxana are buried together.

The main idea consistently and very expressively developed throughout the narrative is that of the vanity of all earthly greatness. For the reader, however, who could undoubtedly appreciate the hero’s bravery and nobility and love him for it, Alexander’s fate after death remained unclear. The author made Alexander believe in a single god, but could not turn him into a Christian or a believer in Judaism in his religious views. Does the hero go to heaven or hell? The compiler of the Russian redaction adds a typical note that was not in the Greek and South Slavonic texts, saying that after Alexander’s death an angel appeared and carried away his soul.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature