Historical Narrative. Fifteenth-Century Chronicle Compilations

Historical Narrative. As in the preceding period the main works of historical narrative in the fifteenth century were the chronicles, the compilations of Russian history.

Fifteenth-Century Chronicle Compilations. Unlike those of previous years, the fifteenth-century compilations have come down to us not only in later manuscripts, but often in the original or in redactions made shortly afterwards. The similarity of the main text of these redactions enables us to establish with reasonable accuracy their common sources, the chronicle compilations.

The finest work of fifteenth-century Russian chronicle-writing that influenced the whole subsequent development of All-Russian and Novgorodian chronicle-writing was the compilation which formed the basis for two chronicles (the Sophia First and the Novgorod Fourth) and is known to specialists as the compilation of 1448. The text of the two chronicles coincides up to 1418-1425, consequently their common protograph (source) must have been compiled after 1425, i.e., probably during the bitter struggle for the throne of Muscovy between Grand Prince Basil II (the Blind) and his relatives, the Galich princes Yuri and Dmitry Shemyaka and Prince Ivan of Mozhaisk. It was this struggle which made the chronicler (who was probably connected with one of the metropolitans of Russia) attack princely feuding with special fervour, appeal for unity in the struggle against Mongol overlordship that had still not been cast off, and combine extensively in his compilation the chronicle-writing of Novgorod and North-Eastern Russia (Vladimir and Moscow). Already chronicles of earlier times had contained information about events in neighbouring principalities but these were only isolated reports, often very brief (very little was said in Vladimir and Moscow chronicles about events in Novgorod, and even less in Novgoro- dian chronicles about the affairs of Vladimir-Suzdal; the chronicle- writing of Tver and Pskov developed in isolation). The compilation of 1448 combined Novgorodian and Vladimir-Moscow chronicle-writing, with large passages from the chronicles of Tver and Pskov and reports from Suzdal and Rostov. We have already mentioned the tale of Michael of Chernigov, the Tver account of Michael, son of Yaroslav, and of Shchelkan, the Pskov tale of Dovmont and the Novgorodian account of the battle on the Lipitsa. In All-Russian chronicle-writing all these accounts were included in the compilation of 1448 and borrowed from it for other chronicles of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The compilation of 1448 made use of a number of chronicle sources (Novgorodian, Vladimir, Southern and, possibly, Rostov chronicles) to give lengthy accounts of the battle on the Kalka (with a reference to the bogatyr Alexander Popovich and the “ten brave men” who perished with him) and Batu’s invasion. The extended accounts of the struggle against the Mongols under Dmitry Donskoy, the Battle of Kulikovo, the invasion of Tokhtamysh, and the Life of St Dmitry Donskoy, appeared for the first time in the compilation of 1448. Taking as a basis the brief and completely factual account in The Trinity Chronicle of the Battle of Kulikovo, the compilation of 1448 stressed in particular the treachery of Oleg of Ryazan, a “villainous murderer” and “Moslem accomplice”, contrasting him with the figure of the pious Dmitry. The original short account of Tokhtamysh’s invasion in 1382 was also rewritten: concrete details of the town’s defence were added, for example, the story about the cloth merchant Adam who caught sight of a high-born Mongol from the town wall and with one shot from his cross-bow “sent an arrow through his wrathful heart”, and the description of the underhand way in which the Mongols captured the city.

A single idea runs through all the stories in the compilation of 1448 that were borrowed from other compilations or included in chronicle-writing for the first time, namely, the need to renounce fratricidal feuding and unite against the external enemy. This is why the short account of Svyatopolk’s murder of his brothers Boris and Gleb in earlier compilations was replaced here by a detailed vita text, the story of the murder of Andrew Bogolubsky is supplemented by a condemnation of the murderers who acted against their “benefactor and master”, and the account of the battle on the Lipitsa is supplemented by an imaginary speech by the boyar Tvorimir on the need to submit to the senior in line; the same ideas were expressed in The Life of Michael of Tver and other tales in the compilation of 1448. Against the background of the feudal war of the mid-fifteenth century all this was of great political relevance.

Compiled before the final conclusion of the feudal war, the compilation of 1448 began to be revised shortly after it appeared. Its text has been conveyed most closely by The Sophia First Chronicle; however the final section of the 1448 compilation, that contained an account of the feudal war and presumably reflected the neutrality of the chronicler on the question of Basil II’s struggle against his rivals, has been altered even in The Sophia First Chronicle. After Basil the Blind’s victory the concluding section of the compilation of 1448 describing his reign and struggle with his rivals was omitted (earlier redaction) or greatly condensed (later redaction). In The Novgorod Fourth Chronicle different changes were made. This chronicle was compiled in Novgorod, which by then had adopted a hostile attitude to Moscow and gave refuge to Basil the Blind’s defeated rival, Dmitry Shemyaka. The basic text of the compilation of 1448 was supplemented by many purely Novgorodian additions (about mayors of Novgorod and events in Novgorod), and the long stories were abridged.6

The first extant chronicle compilations of the grand princes of Moscow date back to the 1470s.

The earliest is a compilation of the early 1470s which has survived in the Nikanor and Vologda-Ferm chronicles. Taking as its basis the compilation of 1448, the grand prince’s chronicle carefully removed all references in it to the fact that the Novgorodians invited the princes they liked to rule and drove out those who displeased them. Instead of “they enthroned him in Novgorod” or “they drove him out of Novgorod” it says that such-and-such a prince “came to Novgorod” or “left Novgorod”. Moreover, the grand prince’s chronicle of the early 1470s contains an account of Basil II’s struggle for the throne that is highly sympathetic to this prince. The story of the conspiracy of his opponent Dmitry Shemyaka and Ivan of Mozhaisk, who imprisoned Basil in 1446, is described particularly vividly (and possibly based on Basil the Blind’s own recollections). Basil hid in the church of the Trinity Monastery, but not expecting to be allowed to take refuge there, himself came out, “praying and shouting fit to choke”. Ivan of Mozhaisk called to one of his boyars, “Seize him.” Basil was thrown into a “bare” (uncovered) sledge and taken to Moscow to be blinded.7

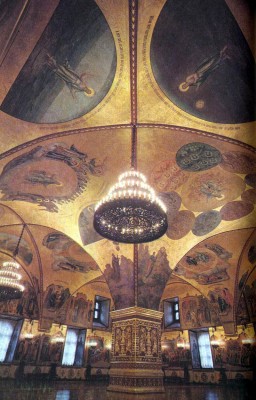

In 1479 a new grand prince’s Moscow compilation was made. By now Novgorod was finally joined to Moscow; unlike the compilation at the beginning of the decade, that of 1479 did not conceal the existence of Novgorod’s former liberties, but noted and condemned them outright: “For such was the accursed custom of these treacherous folk.” The Moscow compilation of 1479 ended with an account of the final submission of Novgorod and the building of Moscow’s main church, the new Cathedral of the Assumption.8

Apart from the chronicle-writing of the Moscow grand principality in the latter half of the fifteenth century, local chronicle-writing continued (in Novgorod up to the 1470s, in Tver up to the 1480s and in Pskov up to the sixteenth century), together with chronicles compiled independently of the grand prince, most probably in the monasteries. The most striking of the latter is The Ermolin Chronicle, the only extant manuscript of which appears to have been commissioned by the eminent Moscow architect and builder Vasily Ermolin (it contains a list of the buildings erected by him). The Ermolin Chronicle and others similar to it (abridged compilations of the late fifteenth century) appear to be based on a compilation made in the White Lake Monastery of St Cyril in 1472. This compilation did not oppose the unification of the Russian state by the princes of Moscow. On the contrary, it regarded the Prince of Moscow as “the great sovereign of the universe”; but it strongly condemned the prince’s cruelty and his military commanders’ abuses. Thus, it relates how Dmitry Shemyaka fled after his defeat to Novgorod and was poisoned by his own cook, at the instigation of a secretary from Moscow. When Basil the Blind heard that his enemy had been killed he was so delighted that he promoted the messenger to a higher rank. Here too it describes how mercilessly Basil dealt with the courtiers of Prince Basil of Serpukhov whom he had imprisoned—he ordered them to be “executed, beaten and tortured, and dragged around by horses”. But the most outraged account in The Ermolin Chronicle is of the annexation of the Yaroslavl lands, which the grand prince seized for himself, giving the princes of Yaroslavl possessions in other, more remote areas. The chronicler begins this account by mentioning a quite different subject. He describes how the relics of local saints “appeared” (i.e., were found) in Yaroslavl, and how these relics began to “forgive”, (i.e., heal the sick and crippled by supposedly forgiving them their sins). But then the chronicler remarks that “the appearance of these miracle-workers did not bode well for the princes of Yaroslavl: for they bade farewell to their patrimonies forever”. He adds wrily that then a “new miracle-worker” appeared in Yaroslavl, the grand prince’s lieutenant, whose “miracles” it is impossible to “describe or count” for he was “the very tsyashos incarnate” (the word tsyashos was an euphemism for “devil”).9 The opening part of the White Lake Monastery of St Cyril compilation of 1472 (up to 1425) is not found in The Ermolin Chronicle: it has been almost completely replaced by a text similar to the Moscow compilation of 1479. But we can get some idea of this part of the White Lake Monastery of St Cyril compilation from the abridged compilations of the late fifteenth century: for example, they contain a fuller version than the Sophia First and Novgorod Fourth chronicles of the Rostov tales about the bogatyrs Alexander Popovich and Dobrynya, who are said to have fought not only in the Battle on the Kalka, but also in the battle on the Lipitsa in 1216.

Another chronicle compilation that was independent of the grand prince and compiled at the end of the 1480s has survived in the Sophia Second and Lvov chronicles. This compilation was highly critical of Grand Prince Ivan III, in particular, his attempts to remove the head of the Church, Metropolitan Gerontius, from office, but the compilation was not a metropolitan chronicle: the metropolitan himself is also criticised here (for lack of respect for the burials of his predecessors). It includes a number of literary works, among them Afanasy Nikitin’s Voyage Beyond Three Seas. It also condemns Ivan Ill’s oppression of his brother princes and the boyars of Tver, the help which Ivan gave to the Crimean khan who looted Kiev (then part of Lithuania) and Ivan’s indecision during the final invasion by Ahmat, the khan of the Horde. When Ivan decided against doing battle and returned to Moscow, the townspeople voiced their discontent with a prince who was handing them over “to the khan and the Mongols”. Possibly fearing that the townspeople would plot against him, Ivan III marched against the khan (the latter was forced to retreat, marking the end of the Mongol overlordship in 1480).10

In the late 1480s independent chronicle-writing ceased in the Russian state (except in Pskov); from then onwards all Russian chronicles were based on the chronicle compilations of the grand princes of Moscow.11

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature