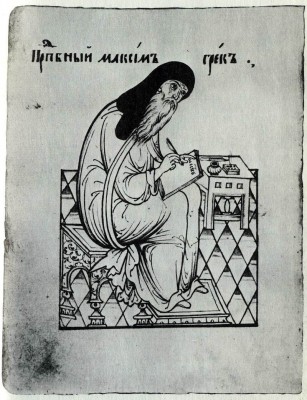

Maxim the Greek

The subjects raised by Vassian Patrikeyev attracted other sixteenth-century publicists as well. The most educated among them was undoubtedly Michael-Maxim Trivolis, who became known in Russian as Maxim the Greek. Today we know quite a lot about the life of this educated monk. Acquainted with many eminent Greek and Italian humanists of the Renaissance, Michael Trivolis went to live in Italy in 1492 and worked with the famous publisher Aldo Manucci. Shortly afterwards he renounced his humanist interests and entered a Dominican monastery. A few years later he returned to the Orthodox Church, became a monk at Mount Athos with the name of Maxim and in 1518 was summoned by Basil III to Moscow.29

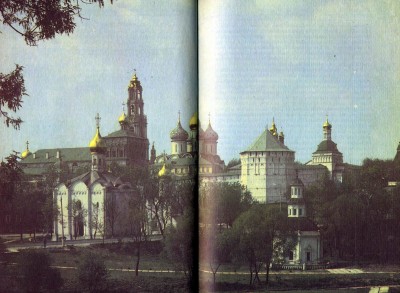

Maxim the Greek did not forget about his humanist past: in Russia he wrote of the Aldo Manucci printing-house and the University of Paris; he was the first to announce the discovery of America in Russia. But he was now strongly opposed to the ideas of the Renaissance. He cursed the “pagan doctrine” embraced by the humanists, from which he himself might have perished had not God “visited” him with “his grace”.30 The warnings that Maxim delivers to his Russian readers against taking an interest in Greek writers (Homer, Socrates, Plato, and the Greek tragedies and comedies) are worthy of attention. They testify to the fact that such interests existed among certain Russian scribes of the period (Theodore Karpov, for example, with whom Maxim corresponded). But for the officials of the RussianChurch (such as Metropolitan Daniel) Maxim himself seemed a highly suspicious character: he was twice tried by a church tribunal (in 1525 and 1535), imprisoned and exiled. Maxim was charged with heresy and with refusing to acknowledge that the Russian Church was independent of the Patriarch of Constantinople, and he was exiled first to the Volokolamsk Monastery, and then to Tver. Only after the death of Basil Ill’s widow, Yelena, and the retirement of his main persecutor, Metropolitan Daniel, was Maxim able to resume his literary activity and declare his innocence, but all his requests for permission to return to Mount Athos remained unanswered. In the early 1550s Maxim was moved from Tver to the Trinity Monastery and virtually rehabilitated; he was drawn into the struggle against the heresy of Matvei Bashkin. He died in the middle of the 1550s.

The ideas of the Non-Possessors are expressed in a number of Maxim the Greek’s writings. Among them is The Awesome and Edifying Tale of the Monk’s Life of Perfection, The Discourse of the Mind and the Soul, The Sermon on Repentance and The Dispute of the Covetous Man with the Non-Covetous Man. In them he described, inter alia, the sad lot of the peasants whom the monasteries drove off their lands for non-payment of debts, or sometimes refused to let them leave, demanding that they work the land and pay “the fixed quit-rent”. If any of them, Maxim wrote, exhausted from “the heavy burden of labour and toil constantly imposed upon them by us, wishes to move to another place, we do not let him go, alas, if he has not paid the fixed quit-rent…”

Whereas Maxim’s themes are in many respects reminiscent of Vassian’s, the literary styles of the two polemicists are not alike. Maxim eschews the irony to which Vassian has recourse, and also his everyday touches. Maxim’s language is a literary, bookish. It is not colloquial speech, but a foreign tongue which the Greek monk learned in middle age. Long phrases of complex construction are typical of it.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature