The Correspondence of Ivan the Terrible with Kurbsky

The most important place in Ivan the Terrible’s writing belongs to his correspondence with Kurbsky. Born of a noble family (related to the princes of Yaroslavl) and a member of the governmental group of the 1550s known as the Select Council, who took part in the Kazan campaign, Andrew Kurbsky fled from Russia in 1564, fearing the tsar’s disfavour. From Polish Livonia he wrote a denunciatory epistle to the tsar accusing him of unjustly persecuting the loyal generals who had conquered “the proudest of realms” for Russia. The tsar replied with an epistle almost as long as a book; and that was the beginning of this famous correspondence.35

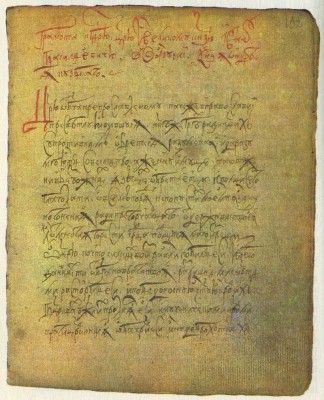

First Epistle of Prince Andrew Kurbsky to Tsar Ivan the Terrible. 17th-century manuscript copy. State Public Library, Leningrad

A feature of this correspondence, distinguishing it from most epistles of preceding centuries, addressed to concrete people, that only later became the object of widespread reading, is that from the very beginning it was of a publicistic nature. In this respect it resembles an earlier epistle, namely, that of the “elders of St Cyril’s” (by Vassian Patrikeyev) to Joseph of Volokolamsk. Of cour.se, the tsar replied to Kurbsky, and Kurbsky to the tsar, but neither expected to persuade the other to change his views. They were writing, first and foremost, for their readers, like the authors of “open letters” in modern literature. Ivan IV’s First Epistle to Kurbsky was called an epistle “to the Russian state” against “those who sin against the cross” (i.e., traitors, perjurers).

In his dispute with “sinners against the cross”, the tsar was naturally guided by the purpose of this polemic. Readers “throughout the Russian state” had to be shown how criminal the boyars denounced in the epistle were.

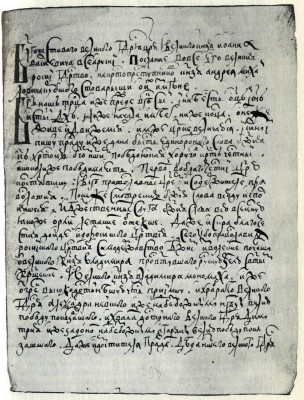

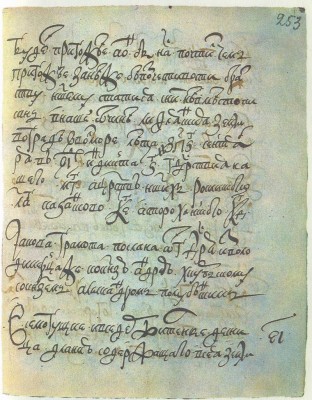

First Epistle of Tsar Ivan the Terrible to Prince Andrew Kurbsky. 17th-century manuscript copy. State Public Library, Leningrad

In reply to the tsar’s First Epistle Kurbsky wrote a brief caustic missive, ridiculing the style and length of Ivan’s epistle; he was unable to send it, however. In 1577 the tsar waged a long and successful campaign in Livonia, conquering numerous towns along the Western Dvina and advancing right up to Riga. After capturing the town of Wolmar (Walmiera) where Kurbsky had fled thirteen years earlier, Ivan sent him a Second Epistle from there. In 1579 during a Polish-Lithuanian counter-offensive Kurbsky wrote his Third Epistle to the tsar.

In his dispute with Kurbsky the tsar defended the idea of absolute monarchy, arguing that the intervention of the boyars and clergy in government was detrimental to the state. The tsar blames his adversary for boyar rule of the 1530s and 1540s, although Kurbsky, who was about the same age as the tsar, could not have taken part in politics at that time. In fact both adversaries were proceeding from the same ideal—the ideas of the Hundred Chapters Council that reaffirmed Russian “purest of pure Orthodoxy” and were merely disputing as to which of them was most faithful to these ideals. Both the tsar and Kurbsky readily appealed to “the Divine Judge” in this dispute. Ivan declared in 1577 that his military successes were proof that Divine providence was on his side, and two years later Kurbsky explained the tsar’s failures in exactly the same way, as Divine judgement.

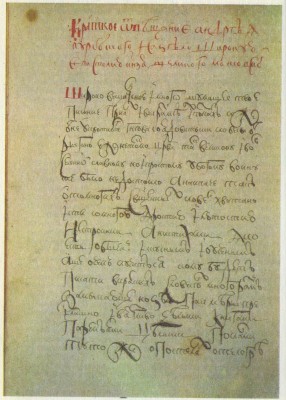

Second Epistle of Prince Andrew Kurbsky to Tsar Ivan the Terrible. 17th-century manuscript copy. State Public Library, Leningrad

An important place in the polemics (particularly in Ivan’s First Epistle) was played by lengthy references to religious literature. But in attempting to prove to readers “throughout the Russian state” that he was right and that “sinners against the Cross” were criminals, the tsar could not confine himself to lengthy quotations from the Church Fathers and rhetorics. He needed vivid, striking examples of the “insults” he had suffered.

And find them he did, painting a moving picture of his orphaned childhood in the period of boyar rule, when the rulers “fell upon one another” and “tossed our mother’s coffers into the State Coffers and kicked out wildly with their feet”. Many of these scenes resemble or are identical to descriptions in the amendments to The Illustrated Chronicle.

Second Epistle of Tsar Ivan the Terrible to Prince Andrew Kurbsky. 17th-century manuscript copy. State Public Library, Leningrad

The scenes of the tsar’s orphaned childhood are particularly vivid; they have frequently been used by historians and artists. The tsar declared that he lacked food and clothing and, most important, the care and attention of elders: “I remember how we would play our children’s games, while Prince Ivan Vasilyevich Shuisky sat on a bench with one elbow resting on our father’s bedstead and his foot up on a chair”, taking no notice of young Ivan and his brother.

This picture can hardly be historically authentic, but its effectiveness, and consequently its literary significance, are riot to be denied. Kurbsky did not ignore this passage in his reply. As well as being Ivan IV’s political opponent, he opposed him in literary matters as well. Mocking the “loud-mouthed and noisy” First Epistle of the tsar, Kurbsky criticised him strongly for introducing these everyday scenes or, as he called them “babblings of foolish women” into literature. The political polemic between the two opponents was accompanied by a purely literary polemic—about the limits of the “scholarly” and “barbaric” in literature.

Andrew Kurbsky. Kurbsky was no less educated than Ivan the Terrible. His grandfather was Vassily Tuchkov, one of the redactors of The Great Menology. It was from the writers of Macarius’ circle that Kurbsky got the idea that literature should be serious and solemn.

We have already noted that in the dispute between Ivan and Kurbsky both opponents had some common points of departure (without such common premises the dispute itself would have been impossible). Both believed that in the middle of the sixteenth century (the time of the Hundred Chapters Council) the Russian state was the land of “most pure Orthodoxy” and each considered himself to be true to this “most pure Orthodoxy” and accused the other of departing from it. That is why Kurbsky called Russia “the Holy Russian Tsardom” and, when he was in Western Russia, defended the Orthodox Church against both Catholics and Russian heretics (such as Theodosius Kosoy) who had fled into Lithuanian Russia and joined the Reformation movement there.

Similar in his social outlook to the Non-Possessors of the first third of the sixteenth century, Kurbsky was nevertheless alien to the literary manner of Vassian Patrikeyev with its humour and colloquial speech. Kurbsky was closer to another writer of the sixteenth century, Maxim the Greek (whom Kurbsky knew before he fled from Russia and deeply respected). Kurbsky’s high-flown rhetoric and complicated syntax are reminiscent of Maxim the Greek and the Graeco-Roman models that he imitated. His epistles to Ivan are a brilliant specimen of the rhetorical style. It is no accident that Kurbsky included a work by the great Roman orator Cicero in one of them. The author’s speech in the First Epistle is written all in one breath, as it were. It is logical and consistent, but completely void of all concrete detail. “Why, oh, Tsar, have you struck down the strong men of Israel and surrendered the generals, given to you to fight your enemies, to all manner of deaths? Why have you shed their victorious, holy blood in God’s churches and made the porches crimson with their martyr’s blood? Why have you thought up unheard-of torments and deaths and persecution for those who wish you well and have laid down their lives for you? Why have you wrongfully accused true Orthodox believers of treason and magic, trying your utmost to turn light into darkness and to call bitter that which is sweet?” Kurbsky asks: “Did they not destroy proud kingdoms and make them subject to you in all realms where our forbears were their slaves? Did they not give you by the efforts of their minds from God the invincible German towns? Have you acted justly in rewarding us, poor creatures, by destroying us in whole families?”36 The lofty oratorical feeling of this address has been brilliantly conveyd by Alexei Konstantinovich Tolstoy, who included a poetic rendering of it in his ballad Vasily Shibanov.

The tsar’s reply, as we know, was not couched in such austere language. Ivan was not afraid of using openly the skomorokh brand of coarse humour. To Kurbsky’s grief-stricken words, “You will not set eyes on my face until the Day of Judgement”, the tsar replies caustically: “Who wants to see an ugly face like that anyway?” As we know, Ivan also included scenes from everyday life in his epistle.

Kurbsky regarded such a mixture of styles and the introduction of “coarse” colloquialisms as the height of bad taste. “It is absurd and ridiculous,” he declared in his reply, to send such an epistle “to scholarly, learned men”, and particularly to a “foreign land where some men are skilled not only in grammar and rhetoric, but also in dialectics and philosophy”. He condemned as improper the references to the tsar’s bedstead on which Prince Shuisky was leaning and another passage saying that until Shuisky stole the tsar’s money he had only one fur coat—“green cotton fabric on marten, and pretty tattered at that…” “And at the same time you speak of beds, and body-warmers and countless other things like the babblings of foolish women; and so barbariously…” Kurbsky comments.

What we have here is a real literary polemic, a dispute as to which style befits an epistle. But whereas in political disputes Kurbsky frequently got the better of the tsar, ridiculing the most absurd of the accusations made against his now executed advisers, in the literary debate he can hardly be considered the winner. He undoubtedly sensed the power of the tsar’s “barbarous” arguments and showed this in another work that he wrote in an entirely different form, that of the historical narrative.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature