The Tale of the Indian Empire

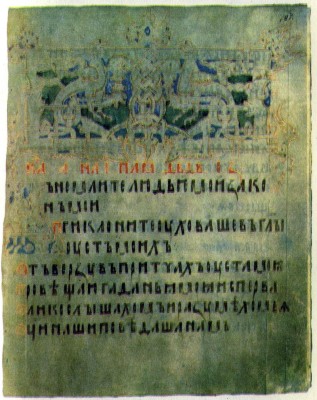

Ever since ancient times India was reputed to be a wonderful, immensely rich land inhabited by strange creatures. One legend said that India was ruled by a mighty ruler called John, who was both emperor and presbyter. To the mediaeval mind remote, mysterious India was a land where people knew neither want nor strife. These fantastic, Utopian views of India were reflected in the legendary Epistle of Emperor John to the Byzantine Emperor Manuel written in the twelfth century. The Latin version of this Epistle formed the basis of a Slavonic translation which is thought to be thirteenth-century. Russian manuscripts of the tale date to the latter half of the fifteenth and the sixteenth century.17

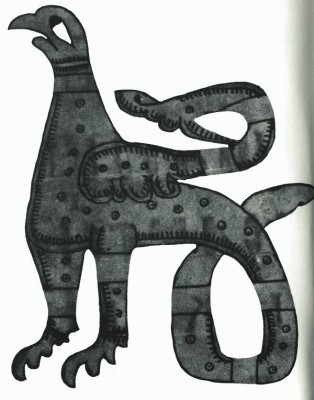

The Tale paints an enticing picture of far-off India. All a person could desire for himself (wealth, universal abundance, peace and security) and for his country (a strong ruler, an invincible army, honest judges, etc.) are to be ‘found there. All this does not simply exist, but is portrayed with the embellishments of the fairy tale. John writes in his Epistle that he is the emperor of emperors, and “three thousand three hundred emperors” are subject to him, his empire is “such that you can walk for ten months in one direction and never reach the other side, for sky and earth meet there”. The emperor’s palace is splendid beyond compare with ordinary earthly ones (“My court is such that you must walk for five days round it…”) and so on and so forth. Apart from ordinary people the Indian empire is inhabited by the strangest creatures (horned, three-legged, many-armed, with eyes in their chest, half-men and half-beasts, etc.). Equally varied and fantastic is the animal kingdom (there is a description of the different birds and beasts and their habits) and many wondrous treasures are to be found in its rivers and below the ground. India has everything, yet there are “no thieves, no robbers, no envious men, because my land abounds in all manner of riches,” writes Emperor John.

John’s unquestionable superiority over the real rulers with which the mediaeval reader could compare this emperor and presbyter of legendary India can be seen not only in the description of his land’s wonders, wealth and power, but also in the foreword to this description. This says that if the Greek Emperor Manuel were to sell his Empire and use the money to buy parchment, the amount of parchment would not suffice even for a description of the wealth and wonders of India.

Some images in The Tale of the Indian Empire recall the bylina about Dyuk Stepanovich. Arriving in Kiev “from India’s rich land” Dyuk boasts of his country’s riches.18 Ilya Muromets and Dobrynya Nikitich set off for India on Prince Vladimir’s orders to see for themselves and find that Dyuk is right and that it is impossible for them to describe the wealth of India. After they have spent three years and three days describing the horses’ harnesses, Dyuk’s mother, “the most venerable widow Marfa Timofeyevna”, says to them:

Oh, you good men, you valuers!

Go you to the fair town of Kiev,

Even unto the Great Prince Vladimir,

And say to the Great Prince Vladimir,

That though he sell Kiev town for paper

And sell all Chernigov town for ink

‘Twill suffice but to describe a few beasts.

Alexander Veselovsky and Vassily Istrin believe that the similarity between the tale and the bylina means they both originated from a common source, a Byzantine poem. One is equally justified in assuming, however, that the bylina was influenced by The Tale of the Indian Empire.

At first glance the descriptions of the wonders of India in the Tale are of a fairy-tale, entertaining nature. However, this fairy-tale nature of the Tale also reflected social and worldly dreams and ideas of the splendour and variety of the world in keeping with the times.

History of Russian Literature

History of Russian Literature